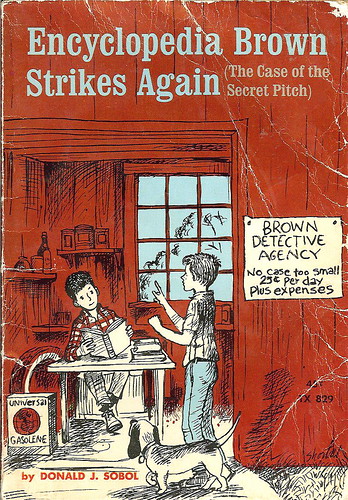

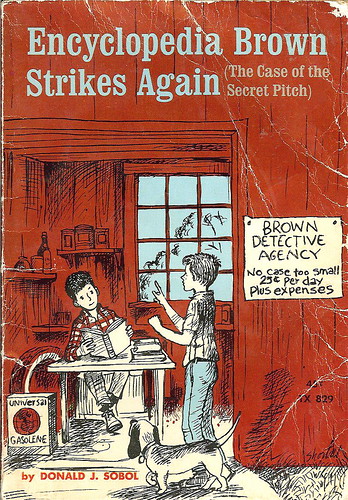

Encyclopedia Brown

Just read that the author died earlier this year.. RIP Donald Sobol!

Cognitive science, mostly, but more a sometimes structured random walk about things.

Pronoun > Definite DP > Indefinite DP/Quantifier > Wh-phrase

Labels: evolution, language, universals

For small groups, the 'notch' parameter sometimes produces notches that extend outside of the box. In previous releases, the notch was truncated to the extent of the box, which could produce a misleading display. A new value of 'markers' for this parameter avoids the display issue.

As a consequence, the anova1 function, which displays notched box plots for grouped data, may show notches that extend outside the boxes.

What circumstances did govern approval and disapproval directed at child utterances by parents? Gross errors of word choice were sometimes corrected, as when Eve said What the guy idea. Once in a while an error of pronunciation was noticed and corrected. Most commonly, however, the grounds on which an utterance was approved or disapproved ... were not strictly linguistic at all. When Eve expressed the opinion that her mother was a girl by saying He a girl mother answered That's right. The child's utterance was ungrammatical but mother did not respond to the fact; instead she responded to the truth value of the proposition the child intended to express. In general the parents fit propositions to the child's utterances, however incomplete or distorted the utterances, and then approved or not, according to the correspondence between the proposition and reality. Thus Her curl my hair was approved because mother was, in fact, curling Eve's hair. However, Sarah's grammatically impeccable There's the animal farmhouse was disapproved because the building was a lighthouse and Adam's Walt Disney comes on, on Tuesday was disapproved because Walt Disney comes on, on some other day. It seems then, to be truth value rather than syntactic well-formedness that chiefly governs explicit verbal reinforcement by parents. Which render mildly paradoxical the fact that the usual product of such a training schedule is an adult whose speech is highly grammatical but not notably truthful (Brown, Cazden, and Bellugi, 1967, pp. 57-58).